Healthcare Access Among Haitian Immigrants in North Carolina: A Qualitative Study

Authors: Deshira D. Wallace, Ph.D; Gimelly Bryant, MPH; Mirlesna Azor, M.Ed.

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

North Carolina has one of the fastest-growing immigrant populations in the United States. Haitians and Haitian Americans (hereafter Haitians) are included in this pattern, with current estimates at 13,129 self-reported Haitians or Haitian Americans in North Carolina. Little is known about how Haitians are navigating the health systems in North Carolina. Therefore, this study aims to use qualitative methods to explore the lived experiences of Haitian adults navigating health systems in North Carolina. These qualitative results can support future targets for intervention to assuage unfair or avoidable differences in care. Themes included: intentional community building, facilitators to healthcare (health insurance, proximity, limited racial and cultural representation), and barriers to healthcare (wait times to establish care, lack of racial and cultural representation).

BACKGROUND

As a proud Haitian-born individual living in the United States, I carry with me both the resilience of my beloved homeland as well as the complexities of navigating life in a new society. For generations prior to my arrival and for years to come, Haitians migrate seeking safety, stability, and opportunity, yet our stories—especially when it comes to health and wellness—are too often left overlooked and even untold. - Interview with Mirlesna Azor, co-founder of Haitians Of The Triangle (HOTT)

Haitian and Haitian American (hereafter Haitian) communities in the United States (US) face unique challenges when accessing health services. Recent studies focused on exploring the health and healthcare experiences of Haitian immigrants and Haitian Americans in the US, primarily South Florida, New York, and Massachusetts, have reported disparate care for perinatal and reproductive care, cancer screenings and survival, diabetes management, and primary healthcare seeking. Facilitators are broadly defined as having health insurance, social support, and culturally tailored health information. Barriers to healthcare include limited knowledge of the condition, financial constraints, and limited access to necessary tests.

Additionally, discrimination, compromised patient-centered care, and a lack of cultural competency can impede health-seeking behaviors. A study in Boston, which aimed to improve informed shared decision-making about birth options after previous C-sections for Haitian Creole speakers through group counseling, highlights the importance of language equity. The study recognized that health literacy, language barriers, and deference to healthcare providers could contribute to misunderstandings or limited understanding of health education materials, which impacted care. By using culturally tailored group counseling, the women involved felt more confident in choosing their birth method and felt better prepared because the open discussions helped them clarify their feelings, ask questions, and overall felt more empowered. Beyond perinatal care, a qualitative study of Haitian American immigrants in the Northeast explored the challenges of effectively managing type 2 diabetes. The study results indicated that improving type 2 diabetes management is supported by family and social support, optimism and hope, and barriers such as discrimination, financial strain, and psychosocial stressors. The study suggests that more involved and collaborative approaches are needed to fully support and improve health and well-being for Haitian communities.

The US Southeast, which includes several “new destination states” for immigrants, including Haitians, is another important geographical location to explore, even if immigrant populations are not historically well established compared to South Florida, New York, and New England regions. There, resources remain uneven, and these barriers are especially sharp. However, one major barrier exists in supporting Haitian health in “new destination states” such as North Carolina. The barrier is data availability. While there is an increased presence of the Haitian community in North Carolina, data are not readily available to detail the demographic shifts happening in the state.

While Census data are catching up to the reality of demographic changes in the state, there remains a need to proactively understand the experiences of Haitian and Haitian American migrants to North Carolina to support community members, advocates, health providers, and policymakers in constructing an environment that is inclusive of this community. Therefore, we use a descriptive qualitative study to explore the lived experiences of navigating healthcare systems for Haitian adults living in North Carolina. Although the goal of qualitative inquiry is not generalizability, its value lies in documenting current experiences in depth, identifying gaps, and informing context and culturally specific solutions.

ANALYSIS

Setting

North Carolina Immigration Snapshot (ACS 2023; Census 2020)

Key population, composition, language proficiency, and county concentration metrics.

Population and Immigrant Share

Native-born with Immigrant Parent

Primary Heritage Countries

- Mexico

- India

- Honduras

- China

- El Salvador

English Proficiency

County Concentration

Haitian Community (Census 2020)

Interpretation

North Carolina is a high-growth new destination state where immigrants represent a sizable share of residents, are concentrated in major metro counties, and include emerging communities such as Haitian immigrants and migrants.

Data notes: Figures are drawn from ACS 2023 and Census 2020 as stated in the paragraph. The Wake+Durham share (23.5%) is computed as 217,400 ÷ 923,923 and shown as an approximate proportion for visualization.

Study Design and Data Analysis

Between November 2023 and December 2024, participants were recruited using purposive sampling to select adults who could speak to their experiences living in and navigating healthcare systems in North Carolina. Recruitment involved a combination of online postings, suggesting people in interviewees’ networks to participate in the study (snowballing), and working with key local organizations, primarily Haitians of the Triangle (HOTT), to share research project details.

Participants were eligible if they:

Self-identified as Haitian or Haitian American

Identified as Black

Were 18 years of age or older

Had resided in North Carolina for at least one year

Had experience engaging with healthcare services in North Carolina

Could participate in English or Haitian Creole

Inclusion criteria were broad, given the formative nature of this study. Recruitment continued until thematic saturation was reached (i.e., no new information was introduced from participants). All participants completed written consent and participated via Zoom or phone. The study protocol was approved by the University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board.

In total, we conducted 15 audio-recorded interviews, which were transcribed and analyzed in the interviewer’s native language. Transcriptions were in English, and 14 of the 15 were based on the English-language interviews. One interview was conducted in Haitian Creole and reviewed by our bilingual author and translated into English for the broader team. Interviews lasted between 90-120 minutes.

Additionally, after each interview, we wrote field notes that included general perceptions of the interview and initial themes. Thereafter, we coded text related to healthcare services in a qualitative data analysis software (ATLAS.ti). Coded text was further analyzed in matrices to examine codes across participants. Using a health equity lens, we explored patterns across individuals, allowing for the development of themes involving health needs, health services, and healthcare utilization. Preliminary results were shared verbally with Haitian community members as a form of member-checking.

Participants and Demographics (N = 15)

Snapshot of participant characteristics referenced in Table 1, plus a summary of the study’s major themes.

Quick Snapshot

Gender

Education

Interview Language

Although most interviews were in English, many participants reported Haitian Creole as their preferred home language.

Preferred Language in the Home

Urbanicity in North Carolina

Five participants lived in rural parts of the state; the remainder lived in urban settings.

Internal Migration (Prior U.S. Residence)

Major Themes Identified (Qualitative Analysis)

- Community building as part of health and wellbeing

- Facilitators to healthcare seeking

- Barriers to healthcare seeking

Community & Making Space for Responsive Health

Many participants (n=10) shared how moving to North Carolina for professional and educational opportunities made them yearn for their culture and sense of community. Through experiencing the lack of or perceived disjointed Haitian representation in North Carolina compared to where they migrated from, many participants must be more intentional in creating Haitian spaces for community building and information sharing. For example, one participant explained creating gardens that serve Haitian and other diasporic communities that allow for the cultivation of familiar foods that can serve to learn about way culturally-sensitive dietary behaviors:

“We are wanting to serve the Latino, the African, the Haitian community and really grow the fruits and vegetables and mushrooms that our culture likes to use them in the food and that is truly the purpose of [the organization] it’s to serve service and provide produce to our international community [… ] I’ve been talking to a couple of chefs that do a lot of Caribbean cooking [...] Cause it’s one thing to tell people we need to eat healthier and eat better food with no pesticide no GMO‘s but if people don’t know how to make it and make it where it taste wonderful and understand what it’s supposed to taste like right they’re never going to convert so we gotta make it an experience.” -Late 50s, woman, Haitian-Dominican American

While there was a general sense of disconnection across participants, many explained how they formally and informally began to build a foundation of community and advocacy that can support (1) awareness that Haitians and Haitian Americans are increasingly residing in North Carolina; (2) community-led interventions for health behaviors (i.e., diet) and wellbeing (i.e., reduced feelings of isolation); (3) culturally-relevant programming; and (4) providing referrals to vetted health services.

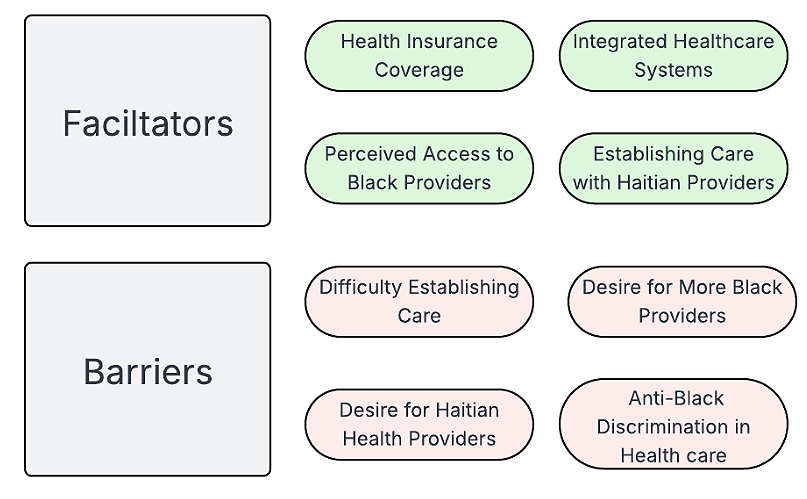

Healthcare Services

Below, we detail the major themes focused on facilitators and barriers to healthcare access. All the participants had access to health insurance through their workplace or university and were recently engaged in health care of some kind. Therefore, they could speak about their healthcare experiences in the state (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Facilitators and Barriers

Figure generated by the authors

Healthcare Services Facilitators

The major facilitator for all participants in this study was access to health insurance. Many participants shared that health insurance coverage allowed them to access all the preventive and specialty services they needed. An additional facilitator was their ability to navigate within one healthcare system, whichever they chose, to obtain referrals to specialists. A few (n=4) participants expressed preferences for certain health systems over others due to geographic proximity, perceptions of the number of Black healthcare providers available, potential access to Haitian providers, and recommendations from other Haitians in the area. As one early 20s Haitian American woman born in North Carolina explained:

"I made a conscious decision a couple months ago that I want all my providers to be Black women. So that's really important to me. And another thing that's also good at [my health system] is that they have a lot of Black physicians working in the healthcare system, and they have a lot of Haitians working in the healthcare system. So, my primary physician is a Haitian woman."

Similarly, three participants spoke highly about having a doctor who reflected their racial background (i.e., racial concordance) and their cultural background (i.e., cultural concordance) not only for themselves but for their family members. One participant explained the benefits of having an obstetrician/gynecologist for his wife while she was pregnant, and how similar it felt to when they lived in the Northeast:

“Here, we had a physician for when we were having our baby that worked well, and that's why we picked [healthcare system] because they had a Haitian gynecologist." -Mid-40s, man, Haitian

Ultimately, participants noted an ease in navigating their selected healthcare system, facilitated by their health insurance coverage and their choice of providers, particularly if those providers aligned with key aspects of their identity.

Healthcare Services Barriers

There were three participants who noted that they did not experience any barriers to care. However, all other participants shared a range of barriers. While all participants had health insurance coverage, health insurance coverage alone does not ease the long wait times to establish care, as described by a Haitian American woman in her mid-20s arriving from the Northeast over one year prior:

"I've sought healthcare, and it's just not been working out. First, I don't know. I know about my plans but trying to find a doctor it's been so difficult. Everybody is like, "Oh, we're not taking any new patients." I'm like, dang, if I was really sick right now, where would I go? I still don't have a doctor or primary health provider because everybody is booked or not taking patients."

While racial and cultural concordance was a facilitator for a few participants, the majority of participants noted a desire for racial concordance, specifically wanting a Black healthcare team (from their primary care provider to their dentist and specialists). However, as they noted that there are fewer Black healthcare professionals in their healthcare systems, the wait times were either too long or these specific healthcare professionals were no longer taking new patients. This perception of the lack of Black healthcare providers is in line with national trends. A 2025 Kaiser Family Foundation report stated that while 5.7% of all physicians in the country self-identify as Black, the largest gap in underrepresentation is in the Southeast – a region with the largest gap between the total Black population and Black physicians compared to the rest of the country.

There was a further intersectional interest among women participants in having a Black woman as a doctor, particularly as a primary care provider or for reproductive care (i.e., gynecologist/obstetrician, nurse midwife). Also, several participants mentioned that if they could have a Haitian doctor to account for the cultural concordance and support language preferences, that would be ideal. However, all participants understood the structural limitations of having a care team that reflected all their identities in a new destination state like North Carolina.

In relation to a desire for racial and cultural alignment between patients and healthcare professionals, language access came up as a concern. As one participant, a mid-40s Haitian man, noted when speaking about the possibility of trying to move his grandparents from the Northeast to North Carolina:

“I would say, while I’m pretty fluent in English, I always tend to go to Haitian physicians. And I couldn't explain why. Or at least I'd like to know that [Haitian physicians] are available. But that's just not the case [in North Carolina]. My grandparents wanted to move them here with us, but I'm like, "They're not going to go to these American physicians where they have to speak English and don't understand." I don't know why-- my grandpa, he gets so annoyed having to translate for him, so that's a barrier."

Finally, a few participants spoke of how the healthcare system as a whole is a barrier to care for Black people like themselves due to anti-Black discrimination and racism. Therefore, they must be more vigilant and fight harder to be taken seriously in an inherently biased system.

"Acknowledging I'm a Black woman and I have Black woman needs and being very aware of their biases. I tend to try to look for Black female doctors. But even then, they're still being taught in a system that is medically racist. So even if they try their best, they are still in a system that's like that. So just being very mindful of me being a patient as a Black woman.” -early 30s, woman, Haitian

These participants noted that intersectional concordance alone is not sufficient for quality healthcare when foundational training and practice within healthcare systems reinforce discriminatory practices. These perceptions are in line with published research highlighting that language concordance alone is not sufficient for quality care, as well as racial concordance and gender concordance.

Strengths and Limitations

To our knowledge, the study's strengths are that it is the first qualitative study focused on Haitians in North Carolina. Qualitative methodology allows for an in-depth understanding of the experiences of participants living and navigating North Carolina. This contextual understanding supports a deeper comprehension of the social and cultural contexts that Haitians experience, which goes beyond the limited numeric data available. The results allow researchers to generate new ideas for future studies.

However, there are limitations to the study. Due to the small sample size and the sample demographics, the results are not generalizable to all Haitians in North Carolina. We collected information from highly educated participants who all had access to health insurance. While this reflects the initial arrival of Haitians in North Carolina for professional and educational needs, there is now a population of Haitians arriving directly from Haiti and working in agriculture in rural North Carolina. As quantitative data are generally limited for the Haitian community in North Carolina, it is difficult to determine if our sample is reflective of the current Haitian experience, specifically as it relates to health care access.

In future studies, we will aim to recruit a broader sample to explore the experiences of Haitians arriving from Haiti and those who may not have access to health insurance. Although generalizability is not the purpose of qualitative research, these results support the initial framing of future research to begin collecting quantitative data on Haitian communities across North Carolina.

RECOMMENDATIONS

Integrating data collection to support policy. Given the political instability in Haiti, there has been a rise in Haitian migrants in the US. While North Carolina has seen growth, data on the number of Haitian immigrants and migrants arriving in the state are not readily available, making it difficult to estimate transition trends. Additionally, data on the number of Haitians in North Carolina year over year is not readily available. Thus, specific actions to improve data collection include:

Develop partnerships between state agencies and community organizations to improve data collection methods and validity. A collaboration between the North Carolina Division of Social Services, the North Carolina State Refugee Office, nongovernmental agencies in the state, like the US Committee for Refugees and Immigrants, and community organizations like Haitians of the Triangle (Raleigh-Durham, NC), Triad Haitian Community Association (High Point, NC), and Haitian Heritage & Friends of Haiti (Charlotte, NC), to develop strategies for data collection to improve recording the number of Haitians moving to North Carolina through multiple means (e.g., immigration, migration).

Capitalize on the 2024 OMB Standard Race Question change for disaggregated data. As of April 2024, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) approved a new standard question for race that combines race and ethnicity. While there exist concerns with the move to combine both questions, one output of this change is that under the “Black or African American” category, Haitian is one of the ethno-racial groups that is specifically included in the definition and can be selected. The OMB change in the standard questions can be integrated into official forms in North Carolina to support data collection efforts. There is also a possibility that by the 2030 Census data release, North Carolina will build a more robust database of more recent ethno-racial groups arriving in the state. Of note, while agencies pull data from the Census, these data may be limited as respondents may be afraid to report their immigration status or exact ethnic group, given the rise in anti-immigrant rhetoric and the spread of misinformation and disinformation.

Engage in policy & legislative advocacy. Collaborations between community partners and academic partners, such as the University of North Carolina at Greensboro’s Center for New Carolinians and the Duke University Center for Latin American & Caribbean Studies, to advocate for legislation or policy directives that mandate more detailed data collection at the state level. Additionally, ensuring that civil rights laws, anti‑discrimination laws, and resource allocation rules recognize national origin subgroups as protected and/or in need of specific inclusion to address potential community-level concerns with data collection.

Healthcare services provider shifts reflective of migration patterns. Haitian immigration and migration patterns are extending beyond traditional destination cities and states. To support these variations in migration patterns, healthcare systems need to try to have supportive systems in place to be responsive to their local demographic shifts. This includes having easily accessible and robust language services and defaulting to having pertinent health and social services information translated into Haitian Creole, instead of only to Spanish, as it is common in North Carolina.

Additionally, participants expressed a desire for racial, gender, and cultural concordance when available. For some, this led to excellent care when it was available, or to barriers to care when it was unavailable. Healthcare systems value patient satisfaction. Therefore, they are incentivized to support diversifying their workforce, from training programs to hiring. In addition to hiring practices, the healthcare system in North Carolina must revamp their professional training of healthcare providers to facilitate increased awareness of the needs and preferences of the Haitian community local to them.

Public health training for the needs of Haitian communities. North Carolina is home to a significant number of public health practitioners and researchers who work in the state, across the US, and internationally. However, awareness of the needs of the Haitian community is lacking. Integrating historical and contemporary events and data in the classroom to increase awareness of Haitian history and their experiences in the US can strengthen the training students are receiving in public health. This training can also support anti-discriminatory practices by reducing biases, both consciously and unconsciously present among instructors, professionals, and students. To supplement what is taught in the classroom, schools can be incentivized to align with their accreditors (e.g., Council on Education for Public Health) and the mission for all public schools and universities in North Carolina support the health and wellbeing for all North Carolinians to create practicum or internship opportunities with Haitian-serving organizations such as Haitians of the Triangle, Triad Haitian Community Association, and Haitian Heritage & Friends of Haiti, to facilitate real-world and timely understanding of the needs and opportunities so support the health and wellbeing of Haitian communities across the state.

-

Brédy GS, Schemm JA, Battaglia TA, Murray Horwitz ME. Pre-pregnancy, Pregnancy, and Postpartum Health and Social Concerns of Haitian Immigrants. J Immigr Minor Health. 2025;27(4):641-645.

Moise RK, Balise R, Ragin C, Kobetz E. Cervical cancer risk and access: Utilizing three statistical tools to assess Haitian women in South Florida. PloS One. 2021;16(7):e0254089.

https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0254089

Romelus J, McLaughlin C, Ruggieri D, Morgan S. A Narrative Review of Cervical Cancer Screening Utilization Among Haitian Immigrant Women in the U.S.: Health Beliefs, Perceptions, and Societal Barriers and Facilitators. J Immigr Minor Health. 2024;26(3):596-603.

Sanchez-Covarrubias AP, Barreto-Coelho P, Ravix J, and al. Differences in breast cancer outcomes amongst Caribbean born women in Florida, USA—a population-based analysis. Lancet Reg Health – Am. 2025;52.

Magny-Normilus C, Whittemore R, Schnipper J, Grey M. Exploring perspectives and challenges to type 2 diabetes self-management in Haitian American immigrants in the COVID-19 era: An emic view. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. Published online February 20, 2025.

Akalın N. Immigrant-blind care: How immigrants experience the “inclusive” health system as they access care. Soc Sci Med. 2024;348:116822.

Bispo JAB, Seay J, Moise RK, Balise RR, Kobetz EK. Perceptions of practitioner support for patient autonomy are associated with delayed health care seeking among Haitian immigrant women in South Florida. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2022;33(2):633-648.

Chinkam S, Pierre KA, Mezwa K, Steer-Massaro C, Shorten A. Promoting shared decision making about birth after cesarean in Haitian women. J Perinat Educ. 2022;31(4):216.

Magny-Normilus C, Whittemore R, Nunez-Smith M, and al. Self-management and glycemic targets in adult Haitian immigrants with type 2 diabetes: Research protocol. Nurs Res. 2023;72(3).

Flippen CA, Farrell-Bryan D. New Destinations and the Changing Geography of Immigrant Incorporation. Annu Rev Sociol. 2021;47(Volume 47, 2021):479-500.

Office of Homeland Security Statistics. State Immigration Statistics. US Department of Homeland Security.

https://ohss.dhs.gov/topics/immigration/state-immigration-data/state-immigration-statistics

US Census Bureau. DP02 Selected Social Characteristics in the United States. Accessed December 20, 2025.

https://data.census.gov/table?t=Native+and+Foreign-Born&g=040XX00US37,37$0500000

American Immigration Council. Immigrants in North Carolina. American Immigration Council. 2020. Accessed October 29, 2025.

Neilsberg Research. Haitian Population in North Carolina by County : 2025 Ranking & Insights. August 8, 2025. Accessed November 17, 2025.

https://www.neilsberg.com/insights/lists/haitian-population-in-north-carolina-by-county/#full-list

US Census Bureau. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for the United States, Regions, States, District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2024. US Census Bureau. 2024.

https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest/tables/2020-2024/state/totals/NST-EST2024-POP.xlsx

Strauss A, Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures and Techniques. Sage Publications; 1990.

World Health Organization. Health equity. Published online 2025.

Miller AN, Duvuuri VNS, Vishanagra K, and al. The Relationship of Race/Ethnicity Concordance to Physician-Patient Communication: A Mixed-Methods Systematic Review. Health Commun. 2024;39(8):1543-1557.

NCDDHS. Social Services. NCDDHS. 2025. Accessed November 17, 2025.

NCDHHS. Refugee Services. NC Department of Health and Human Services. 2025. Accessed November 17, 2025.

https://www.ncdhhs.gov/divisions/social-services/refugee-services

USCRI. Who We Are - U.S. Committee for Refugees and Immigrants. Who We Are. 2025. Accessed November 17, 2025.

US Census Bureau. What Updates to OMB’s Race/Ethnicity Standards Mean for the Census Bureau. Census.gov. April 8, 2024. Accessed November 17, 2025.

https://www.census.gov/newsroom/blogs/random-samplings/2024/04/updates-race-ethnicity-standards.html

UNC Greensboro. The Center for New North Carolinians. The Center for New North Carolinians. 2025. Accessed November 17, 2025.

Duke University. Homepage: Center for Latin American & Caribbean Studies. Duke Center for Latin American & Caribbean Studies. 2025. Accessed November 17, 2025.

The Authors

Deshira D. Wallace, PhD (she/her) is an assistant professor at UNC-Chapel Hill's Department of Health Behavior. Dr. Wallace's work is focused on the role of stressors, psychosocial, environmental, and structural, on chronic conditions among minoritized populations. She also works at the intersection of mental and emotional health and physical health. Her work is focused on Latin American and Caribbean populations in the US and rural communities in Hispaniola, in which she uses both qualitative and quantitative methods to explore the role of stress on chronic conditions as well as identity, Blackness, and health.

Ms. Gimelly Bryant, MPH, is a public health professional with experience in supporting research data collection among Latinos and Haitian populations. Ms. Bryant has worked as a community health worker in North Carolina supporting immigrant populations, primarily from Latin America and the Caribbean.

Mrs. Mirlesna Azor, M.Ed., is the co-founder and chair of Haitians of the Triangle, an organization aimed at preserving Haitian culture, fostering community connection, and advocating for Haitian interests in the central North Carolina region. Mrs. Azor is the Academic Coordinator for the UNC-Chapel Hill’s Department of Epidemiology and Nutrition PhD students.

Haiti Policy House is a not-for-profit institution focusing on Haitian public policy issues. Its research is nonpartisan. Haiti Policy House does not take specific policy positions. Accordingly, all views, positions, and conclusions expressed in this publication should be understood to be solely those of the author(s).

© 2026 by Haiti Policy House. All rights reserved.